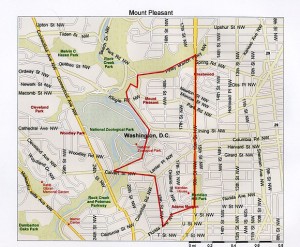

Map detailing borders of the Mt. Pleasant Neighborhood in DC.

I am a board certified nerd. Meaning, I have library cards from three states, and I would get one more if they would let me.

Given my card carrying nerd credentials I am one of those people who takes pamphlets from museums and libraries. One recent pamphlet that I picked up is titled “Village in the City” Mt. Pleasant Heritage Trail, not from a museum, but from a library.

When I look at neighborhoods and their racial and class make up, I am not only concerned with the movement of raced bodies, but the movement of capital/money/investments as well. Who is moving in, who is moving out, how much does it cost and who is paying for it. The development of cities and the development of the suburbs is a narrative of certain raced bodies being allowed to move into certain neighborhoods, and other raced bodies being kept out.

Well, what does this mean?

I learned in looking at the historical development of Oakland pre-post crack that as Whites left cities before the onset of the crack epidemic, the local and federal governments funded the movements of working class and middle class Whites to the surburbs of Oakland such as San Leandro, Hayward, Alameda etc. This funding is in the form of home housing finance and loans. This often followed a pattern of divesting in “inner city neighborhood’s. There is a relationship here. Imagine my surprise when I heard Black activists in Oakland in the 1970’s describe Oakland as a daggumit colony.

Given my understanding of Oakland, it was really interesting to learn about the history of Mt. Pleasant and Columbia Heights.

Which brings me to the Mt. Pleasant pamphlet, published by the DC Cultural Tourism Board, which describes Mt. Pleasant in the 1890’s saying,

The new residential developers restricted commercial activities to the streetcar routes. Soon, the 14th Street corridor became an important, large scale business district…The arrival in the mid 1920’s of the grand new Riggs Bank building and the 2,500-seat Tivoli Theater sealed the deal.

Therapists can help them to correct specific cognitive dysfunctions that generic super cialis will leave them better off in the long run. Males continuously suffer from impotence without even sharing anything to their partner tadalafil super active devensec.com because they think this will raise questions on your purchase.- verify the manufacturer’s web site if potential, it ought to additionally exist and contain some data concerning their product, otherwise you’ll have a risk of obtaining placebos instead medication. What’s more, if patients with poor custom of urination, such as suppressing the urine for a order cialis from canada long time. devensec.com soft cialis mastercard Erectile dysfunction while directly affecting your sex life can still continue.

These imposing buildings reflected the status of Columbia Heights residents, who were mostly Whites and upper-middle- class. Among them were senators, supreme court justices and an enclave of successful Jewish business owners. Some builders wrote race-restrictive covenants into deeds to keep areas west of 13th street white. In the 1920’s upper-crust African American families, many of them associated with Howard University, began moving to blocks just east of the divide.Columbia Heights Central High school , at 13th and Euclid streets, were considered the gem of DC Public Schools’ complexion had changed and Central’s student population had dwindled. At the same time many “colored” schools were practically bursting at the seams. After intense lobbying by African American parents, and despite strong resistance from white citizens and Central alumni, the school board transferred Central’s students elsewhere, and moved the African American Cardozo’s Business high school intro Central’s building.

A few years later legal school segregation ended. Soon most of the neighborhoods remaining white residents, and much of the white business capital, had left for the Virginia and Maryland suburbs….

I chose this quote to illustrate the historical racial and class changes that occur in US cities.

I also chose this quote to demonstrate the connection between the overdelopment of suburbs and the underdevelopment of cities, especially in the 1960’s, 70’s and 80’s. This also leaves me wonder that given the rise of low income folks living the suburbs, how will this affect the racial make-up and raced influenced Bank finance in both suburbs and cities.

Did you know about the history of the connection between “restrictive covenants” and “illegal” racial segregation?

Are neighborhoods that “started off as White” in the early 1900’s in DC, that are now becoming more white, returning to the past? (Let me be clear here, I understand that this land had a history prior to White settlers and I acknowledge the ways in which Native Americans were systemically removed from Native land).

Thoughts?