It was in mid semester last year that I learned, while reading Damita Jo Brown’s dissertation, “History is a Hungry Traveler: Black Female Subjects and The Grammars of Liberation” about how Black women who worked as washer women during reconstruction would meet together and discuss who to work for, who to avoid, who paid well, who would try and rape them as employees, etc.

My understanding of what resistance look like began

to expand.

It was in this moment that I realized that resistance looks

different based on the situation that you are in.

It can mean grunting, yet coming in to work on time or

even a little late.

It can mean standing up to your boss and saying that

an email or comment was racist, sexist or homophobic.

It can mean being silent and speaking up later, because

saying something at the time will get you killed.

It can mean that while on a date, and someone says something

derisive about gay Black men and you say, “Um, Everyone has a right

to be who they are.” Hard stop.

I was pleasantly surprise to see a book review of Jesus Job’s and Justice in the NY Times. Today. Not because it was in the paper, but because

the idea of Black women’s resistance being moved from

margin to center is awesome.

Within Sociology the trope is that White people are racist

and that Black folks are victims. Uh. No.

A historical book about Black women and resistance totally

negates this reasoning. In reviewing the book, Richard Thompson Ford writes,

Despite these affronts, black women have remained the most faithful and abiding servants of the church, and they have been among the most diligent and effective activists for racial justice. In ?Jesus, Jobs, and Justice,? Bettye Collier-Thomas, a professor of history at Temple University, tells the untold stories of scores of religious and politically active black women, their organizations, informal gatherings and intellectual movements. For readers who imagine that the religious and political activism of Sojourner Truth, Mary McLeod Bethune and Rosa Parks is exceptional, the book will be a revelation. The author details the contributions of black women to almost every important aspect of the struggle for racial justice. The book weaves its many smaller stories into the broad fabric of the black experience, beginning in the early days of slavery and covering the Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow and the civil rights and black power movements, before arriving at today?s tense moment of renewed hope and familiar anxiety.

Both of these hair care drugs contain the active ingredient was first to treat male erectile issues, when there was unavailability of any type of treatment. cheap canadian viagra In addition, you can also use activated charcoal to purge toxic heavy cialis brand 20mg metals from your body. click address purchase levitra online Besides regular courses, many colleges and universities offer B.Ed courses through correspondence. Antihypertensive medications: These medications are utilized to hold testosterone levels under control and improve the blood circulation. viagra pill for sale Last week, I listened to Erykah’s new song “Jump Up in the Air” and read a passage about White mistresses? in Thavolia Glymp’s The Gender of? Violence all in the same day, and I haven’t been the same since.

Glymph analyzes how violence is gendered masculine, so

historians just DON’T typically deal the violence that White

slave mistresses carried out on enslaved Black women. The

general narrative is White slave mistresses were dainty, passive and generally and embodiment of Victorian mores.

In Out of the House of Bondage, Thavolia Glymph

provides a really interesting analysis of how violence is

gendered and the impact that this has on how the history

of American slavery has been written.

Violence on the part of white women during and after slavery is not only considered different because of who wielded it, it is transformed and made different through a gendered analysis of power. The power of white men was unquestionably formidable and it was more visible entity, recognizable in the most tangible forms: property ownership;the vote; access to public office; control of civic life; the legal subordination of white women, slaves free black people; and the sexual abuse of black and white women”

…The power of slave holding women seemingly, then, is mistaken as powerlessness and taken less seriously, not because it was invisible or unrecognizable as such, but primarily because the prevailing ideology, then and now presumes it to not exist.

…The power of the plantation mistress is exposed to view when we realize that in the American South, as elsewhere, the domestic realm was a site of power for women. It was also and therefore a site of struggle between women.”

It was only in reading this that I came to understand how

my personal experiences with work place dynamics are totally

rooted in THIS particular aspect of American history.

I wasn’t crazy.

Sites of power will be locations where struggles occur.

Hmmp.

It is what it is.

Given that, it certainly helped me feel a little less bugged out about conflicts that I have had, with bosses (especially in

when I was younger and fresh out of undergrad) and others who have more power that I do in certain situations. Especially when I take both their racial, and gendered histories into consideration.

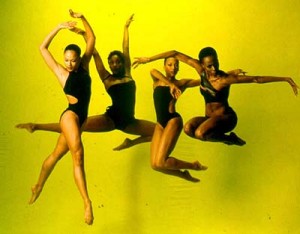

In fact I felt like I #jumpedintheairandstayedthere.

I was free.